How humans invented social organization and politics

For the vast majority of human history, humans lived without “politics” in its modern sense. We inhabited small, mobile bands where everyone knew one another and reached decisions through consensus.

But as our ancestors transitioned from nomadic groups to settled communities, organization became necessary. What began as simple agreements around shared resources evolved into complex systems of governance that would go on to shape entire civilizations.

The egalitarian experiment: lessons from Çatalhöyük

One of the most fascinating glimpses into early social organization comes from Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic settlement in modern-day Turkey that thrived around 7500 BCE.

Unlike the hierarchical cities that would follow, Çatalhöyük was remarkably egalitarian. There were no palaces, no temples, and no grand government buildings. In fact, there weren’t even streets. The houses were packed together like a honeycomb, and people moved across rooftops, entering their homes through holes in the ceiling.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the society was organized along matrilocal and matrilineal lines. Men and women received equivalent nutrition, held equal social status and spent their time doing similar work. There is no evidence of a ruling class. This shows us that social organization didn’t start with someone seizing power. These people managed a population of up to 10,000 people for two millennia without a visible boss. They proved that complex living doesn’t always require a pyramid of power.

Tribes and chiefdoms

As groups grew larger you need a system to maintain society. Different tribes experimented with various models. Some developed “Big Man” societies, where prestige wasn’t inherited but earned through generosity and the ability to organize feasts or defense. Others moved toward Chiefdoms, where social status became hereditary.

The essential shift happened when societies moved from reciprocal sharing (I give to you because you’re my cousin) to redistribution (we all give to a central authority, and they decide who gets what). This was the birth of the state.

The rise of the city-state and the first empires

The transformation accelerated with urbanization in Mesopotamia around 5,000-4,500 BCE. Uruk, recognized today as the world’s first city, emerged as intensive agricultural practices created food surpluses. Maintaining irrigation canals required organized labor, and concentrated populations needed coordination.

Early Sumerian city-states like Eridu, Uruk, Umma, and Nippur developed around temple complexes dedicated to specific gods. These temples, built from mud brick, became the most imposing structures in their cities and served as administrative and economic centers. Each city-state operated independently with its own patron deity, creating a political landscape of competing urban powers.

For the first time, society was divided into specialized classes: priests, soldiers, craftsmen, and farmers. This specialization made these societies incredibly powerful and productive, but it also required a rigid political structure to keep the gears turning.

By 2300 BCE, Sargon of Akkad took this a step further by conquering multiple city-states to create the world’s first empire. Politics stopped being about running a city and turned into the problem of governing strangers spread across enormous territories.

The invention of democracy and its limits

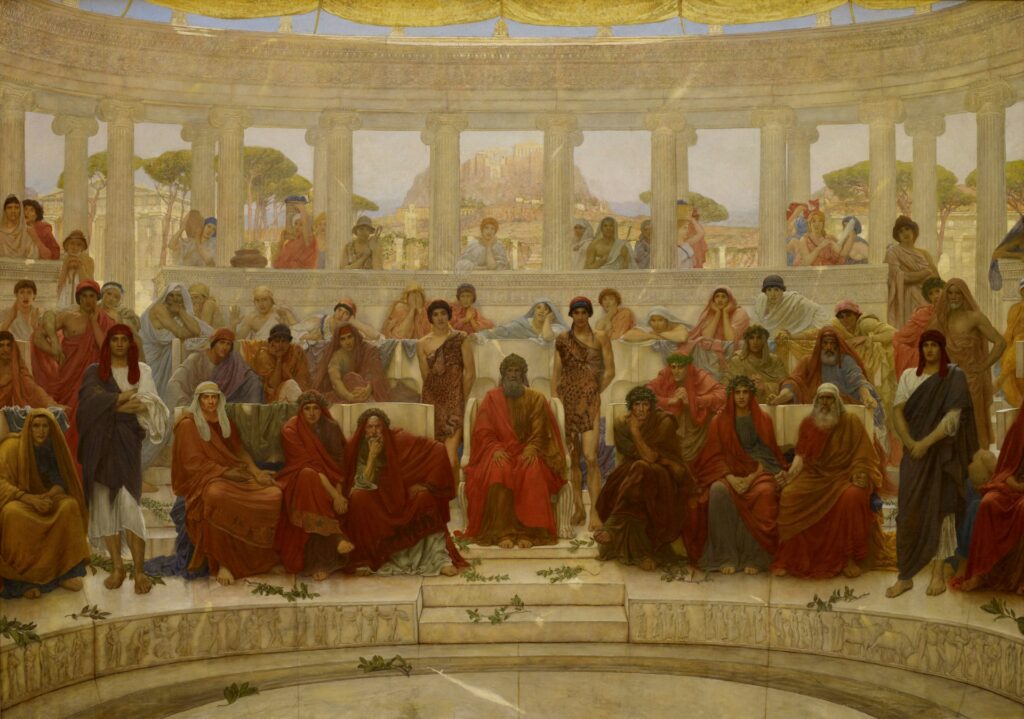

Several Greek city-states, particularly Athens, pioneered democratic governance around the 5th century BCE. Athenian democracy was direct rather than representative, adult male citizens over age 20 could participate in the assembly, and doing so was considered a duty.

But citizenship itself was narrowly defined. Only adult males with Athenian parentage on both sides qualified as citizens. This excluded women entirely, along with slaves and metics (foreign residents) who often formed the backbone of the Athenian economy as artisans and merchants. While revolutionary in allowing citizens direct political participation, Athenian democracy restricted that privilege to a minority of the population.

Despite its flaws, the Greek model introduced a revolutionary idea: that the law should be the master, not a person. Decisions were made in the Ecclesia (an assembly) where any citizen could speak. It was the first time in history that politics became a public debate rather than a royal decree.

The tools of governance

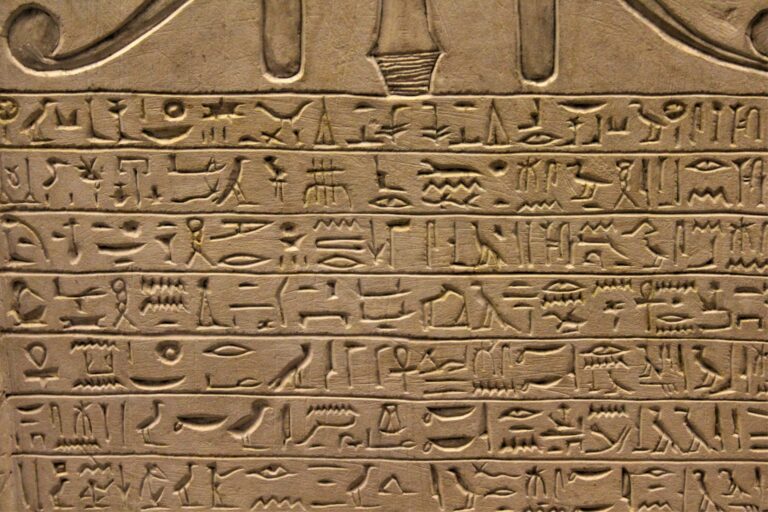

Three interconnected forces enabled ancient political systems to function and endure: writing, religion, and education. Together, they created the intellectual and institutional infrastructure that transformed informal social arrangements into codified states.

Writing transformed politics from oral tradition to permanent systems. The Sumerians invented cuneiform script, which spread throughout the Middle East. Legal codes written in cuneiform provided the first systematic records of laws governing these societies. The Code of Hammurabi remained studied and copied for at least 1,500 years after its creation, serving as a model for legal reasoning across generations.

Religion and politics were inseparable, with religious beliefs shaping political structures while leaders used religion to legitimize their power. Temples controlled vast resources and directly impacted governance. In Rome, colleges of priests played crucial roles in governance, with pontifices and augurs interpreting religious law and omens that directly influenced political decisions. These religious officials even held veto power over certain political actions.

Education completed this triad by producing citizens capable of participating in governance. In Greek city-states, education combined practical literacy with philosophy and rhetoric, skills essential for public debates and leadership. Philosophy taught students ethics and governance, while rhetoric mastered the art of persuasion. This education system cultivated civic responsibility and critical thinking that reinforced democratic participation.

What made it all possible?

A perfect storm of conditions drove the transition from wandering bands to organized states:

- The Surplus: Agriculture allowed us to grow more food than we could eat immediately. This surplus is the foundation of all politics. If you have extra food, you can pay a soldier to protect you or a priest to pray for you.

- Trade: The need for resources like tin, copper, and timber forced different groups to communicate and negotiate. Trade routes became the nervous system of the ancient world, carrying ideas and political models alongside goods.

- Geography: Great civilizations almost always started in river valleys (the Nile, the Indus, the Yellow River, the Tigris and Euphrates). The need to manage water for irrigation required a level of social cooperation that naturally evolved into government.

- Technology: The wheel, the plow, and bronze weaponry changed the stakes of organization. If your neighbor has a bronze sword and an organized militia, you’d better find a way to organize your own people fast.

From tribes to empires

The journey from small communities to vast empires wasn’t linear or predetermined. Çatalhöyük shows that early settled societies could maintain relative equality for millennia, while other regions experimented with kinship-based governance and consensus models. But as populations grew and resources became more valuable, hierarchies offered advantages in coordination and control.

Writing, law, religion, and education became tools for organizing increasingly complex societies, and for justifying the power of those who ruled them. Human political organization arose from practical needs: coordinating irrigation, defending territory, facilitating trade, and resolving disputes. The systems that emerged reflected both human creativity and the specific conditions of their time and place.