Charting the unknown: the evolution and origins of maps

Humanity has always possessed an inherent drive to understand its surroundings. Long before civilizations rose, humans scratched directions in dirt and carved landscapes into cave floors. Driven by the fundamental need to understand and communicate spatial relationships. The history of cartography is a testament to human ingenuity. Born from the need for survival, the complexities of trade, and an unyielding curiosity about what lies beyond the horizon.

When maps emerged from prehistory

It is a common misconception that mapping began with organized civilization. In reality, spatial representation predates writing. Archaeological evidence suggests that prehistoric peoples created rudimentary maps to track migration patterns, locate water sources, and identify hunting grounds.

The oldest known map, a 20,000-year-old three-dimensional representation carved into a French cave floor. It reveals that prehistoric people possessed remarkable abstract thinking, creating a functioning model of their valley complete with rivers and hills

In the Lascaux caves of France, researchers have identified dots that correspond to the Pleiades and the Summer Triangle. Suggesting that the first maps were actually celestial. By carving notations onto mammoth tusks or painting onto cave walls, they created a shared visual language that allowed for collective survival in a harsh, unpredictable environment.

The cradle of cartography

As nomadic tribes transitioned into settled societies, the function of maps shifted from survival to administration and divinity. The Babylonians are often credited with creating one of the earliest known world maps, the Imago Mundi. Dating back to the 6th century BCE. Carved into a clay tablet, it depicts the known world as a circular disk surrounded by “bitter water” (the ocean), with Babylon at the center.

While the Babylonians looked at the world through a theological lens, the Egyptians approached mapping with mathematical pragmatism. The annual flooding of the Nile necessitated a way to redefine property boundaries once the waters receded. Their maps were legal documents, essential for land ownership and the taxation systems that funded the Pharaohs’ empires.

The greek revolution: mathematics and the spherical earth

The Greeks transformed cartography into a science. Anaximander is often cited as one of the first to attempt a map of the entire inhabited world. However, it was Eratosthenes who made the most significant leap. By using the shadows of the sun to calculate the Earth’s circumference with surprising accuracy. He introduced the concept of a spherical Earth to the mapping process.

Later, Claudius Ptolemy produced Geographia, a monumental work that introduced a grid system of latitude and longitude. Ptolemy realized that to represent a 3D sphere on a 2D surface, one needed a mathematical projection. His work remained the standard for over a millennium, providing the foundational logic that would eventually guide the explorers of the Renaissance.

The essential role of maps in daily life and governance

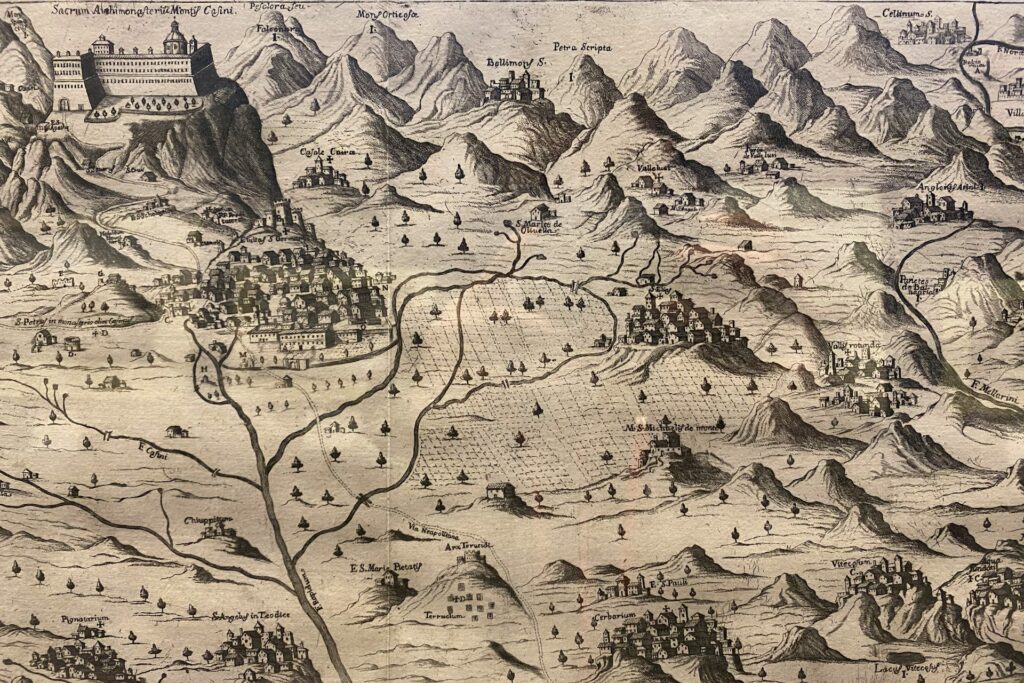

Maps were tools of power. In the Roman Empire, the Tabula Peutingeriana served as a massive road map, spanning the entirety of the imperial highway system. It was essential for military logistics, allowing the rapid movement of legions and the efficient delivery of imperial decrees.

In civilian life, maps became vital for urban planning and resource management. From the irrigation charts of Mesopotamia to the mining maps of the Middle Ages, the ability to visualize the distribution of resources allowed civilizations to scale. Mapping turned the abstract concept of territory into a tangible asset that could be defended, sold, or taxed.

The mastery of time and the compass

The evolution of cartography cannot be separated from the evolution of navigational technology. For centuries, mariners could determine their latitude (north-south position) by looking at the stars, but longitude (east-west position) remained a deadly mystery.

The breakthrough came with the refinement of time measurement. To know how far east or west you had traveled, you needed to know the exact time difference between your current location and a fixed reference point. The development of the marine chronometer by John Harrison in the 18th century was a turning point. For the first time, sailors could fix their position on a map with absolute precision, drastically reducing shipwrecks and lost cargo.

Parallel to this was the introduction of the magnetic compass. Originating in China during the Han Dynasty and later migrating to the West, the compass provided a reliable “north” regardless of weather or visibility. This allowed cartographers to create highly detailed maps of coastlines and ports marked with “rhumb lines” that sailors used to navigate between destinations.

Maritime exploration and the last islands

Maps were the primary catalysts for the Age of Discovery. As European powers sought new routes to the spice-rich East, the demand for accurate charts reached a fever pitch. Cartographers became some of the most valued members of society, often working in secrecy to protect the trade routes discovered by their respective nations.

This era saw the mapping of the “New World” and the gradual filling in of the Terra Incognita. The use of maps allowed explorers like Magellan and Cook to navigate the vast Pacific, leading to the discovery of the last isolated island chains, such as Hawaii and the smaller archipelagos of Oceania.

Interestingly, many of these “discoveries” relied on the existing knowledge of indigenous navigators. For example, the Polynesians used “stick charts”: intricate lattices of wood and shells that mapped wave patterns and currents, to navigate thousands of miles of open ocean long before European contact.

The drivers for the creation of the first maps

The creation of sophisticated cartography was made possible by a specific set of social and economic conditions. The rise of a merchant class in the Mediterranean and Asia created a market for reliable geographical data. Trade was the engine of cartography. If a merchant knew a faster, safer route to a market, they gained a competitive advantage.

Technological advancements outside of navigation also played a role. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg meant that maps could be mass-produced. No longer were they unique, hand-drawn treasures reserved for kings. They became accessible to the rising middle class, fueling a global interest in geography.

Furthermore, the development of paper-making techniques and more durable inks allowed maps to survive the harsh conditions of sea voyages. The social shift toward the Enlightenment, which prioritized empirical evidence over religious dogma, encouraged cartographers to remove mythical sea monsters from their charts and replace them with observed data and mathematical coordinates.

The legacy of the first charts

The transition from cave walls to clay tablets, and eventually to the sophisticated charts of the maritime era, reflects the expansion of the human horizon.

The development of these tools required a rare convergence of mathematical genius, physical bravery from explorers, and the economic pressure of global trade. The ability to measure the Earth and its oceans transformed the planet from a series of disconnected regions into a single, navigable entity, setting the stage for the modern interconnected world.