The history of writing: from symbols to alphabets

The most profound leap in human history was not the mastery of fire or the invention of the wheel, but rather the moment we learned to trap thoughts in physical form. Before the written word, the sum of human knowledge was a fragile thing, tethered to the limits of biological memory and the fleeting nature of speech.

Prehistoric humans used cave paintings and tally marks for tens of thousands of years. These tools helped communicate ideas and track patterns, such as lunar cycles. However, they were not full writing systems. Instead, they functioned as proto-writing. In other words, they were mnemonic devices rather than a true written language. The birth of true writing required a specific set of social pressures: the rise of the first cities, the complexity of mass agriculture, and the logistical nightmare of early bureaucracy.

From marks to true writing

Long before anyone wrote a sentence, humans used marks to count, remember, and claim. In the ancient Near East, small clay tokens represented different commodities: sheep, jars of oil, measures of grain. These were stored or sealed inside clay envelopes as a bookkeeping device. Over centuries, people began pressing the tokens’ shapes into the clay instead of storing the objects themselves. Creating flat tablets with impressed symbols: a bridge between counting and writing.

True writing emerges once marks represent spoken language units like words and syllables. Mesopotamian scripts clearly crossed this threshold for the first time in the late fourth millennium BCE. When early pictograms used for accounting gradually evolved into a script capable of recording names, verbs, and connected phrases. Similar transitions happened later in other regions, but always with the same underlying move: from memory aids to externalized language.

The first civilizations to write

Scholars today usually recognize at least four independent inventions of writing: in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica.

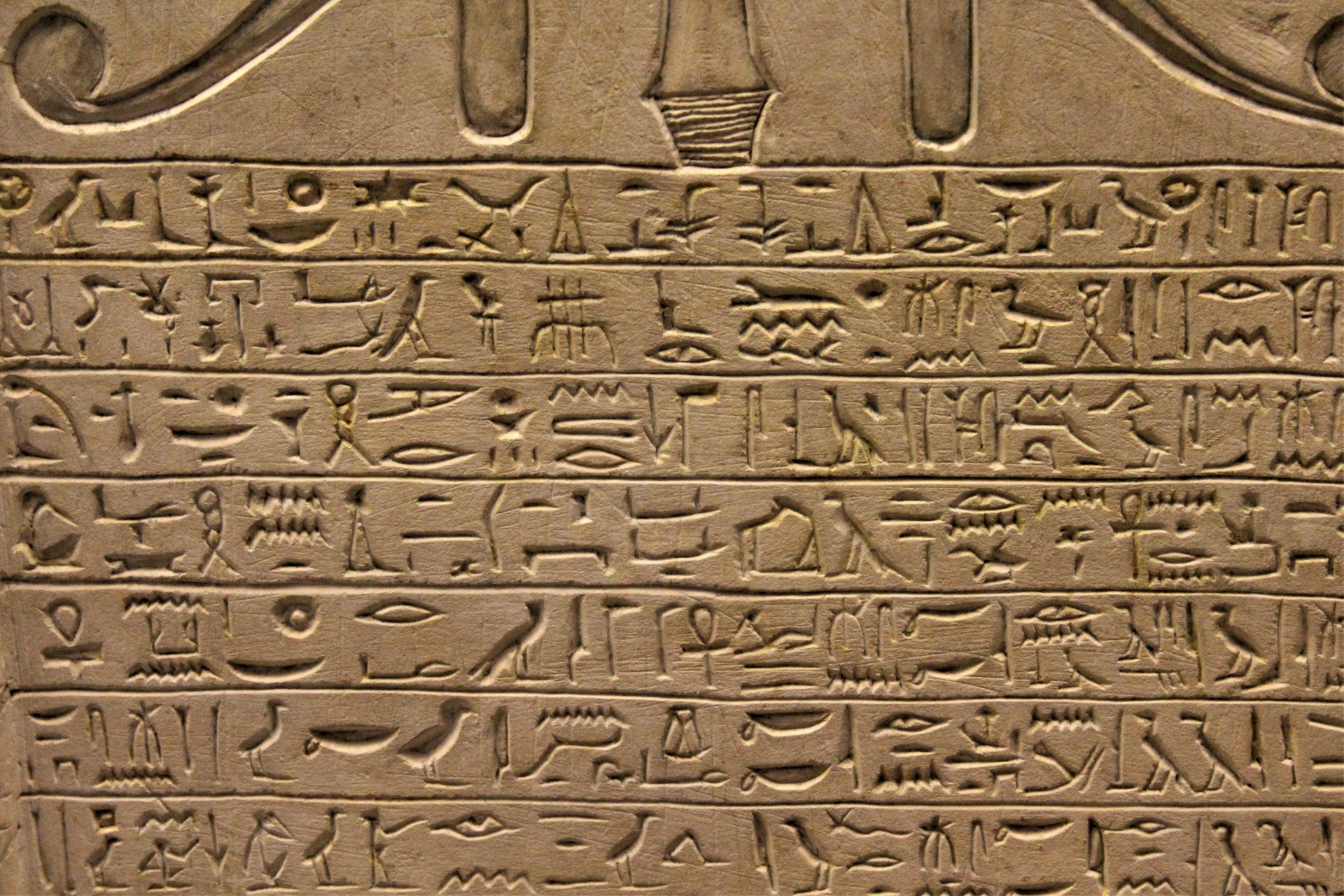

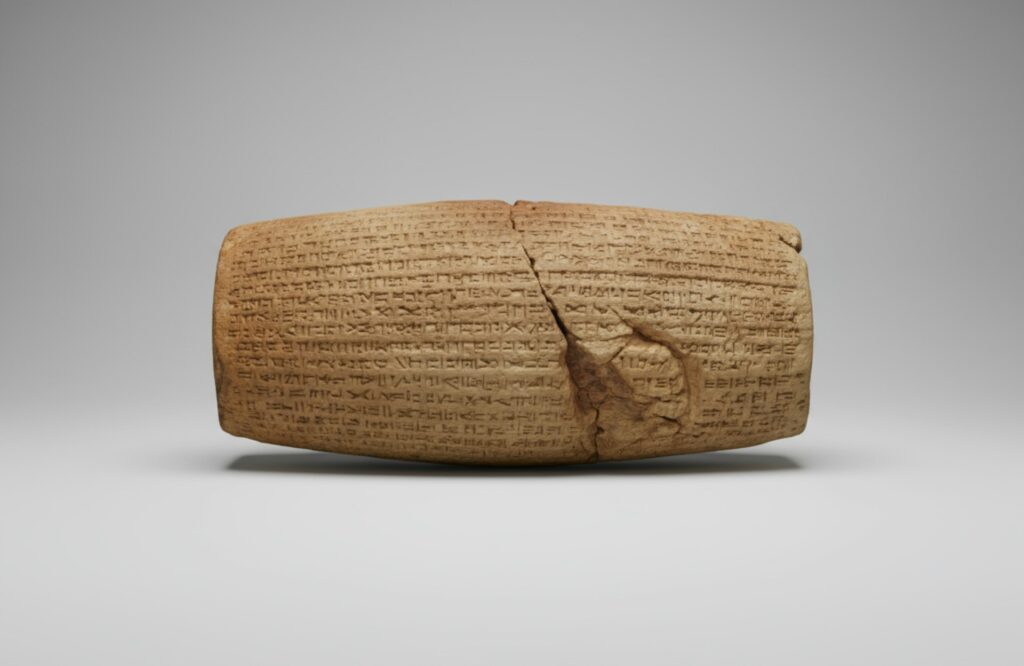

- Mesopotamia (Sumer): Cuneiform emerges around 3400–3100 BCE in the cities of southern Iraq, with the earliest coherent texts by about 2600 BCE. Scribes used a reed stylus to press wedge‑shaped signs into damp clay tablets, which could be dried or baked.

- Egypt: Hieroglyphic writing appears almost simultaneously, around 3250–3200 BCE. But its structure and style differ enough from cuneiform that most specialists see it as an independent invention, perhaps inspired only by the general idea of writing.

- China: The earliest unambiguous Chinese writing is found on oracle bones from the late second millennium, around 1200 BCE (Shang dynasty). Where inscriptions record divinations about royal affairs. These characters already show a complex system that later becomes classical Chinese script.

- Mesoamerica: A distinct family of scripts, including Maya writing, develops between roughly 1200 and 600 BCE. Likely first among the Olmec or related groups and later elaborated by the Maya. These glyphs could encode both logograms (words) and syllables, allowing long historical and ritual texts.

Other scripts, from the Phoenician alphabet in the Levant to Brahmi in South Asia, seem to grow out of contact with earlier systems rather than from scratch. Adapting older ideas to new languages and needs.

The great simplification of writing

Early writing systems were incredibly difficult to learn. Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs involved hundreds, sometimes thousands, of symbols. Literacy was a guarded secret of the scribal class, a “guild” of professionals who held immense power within the state.

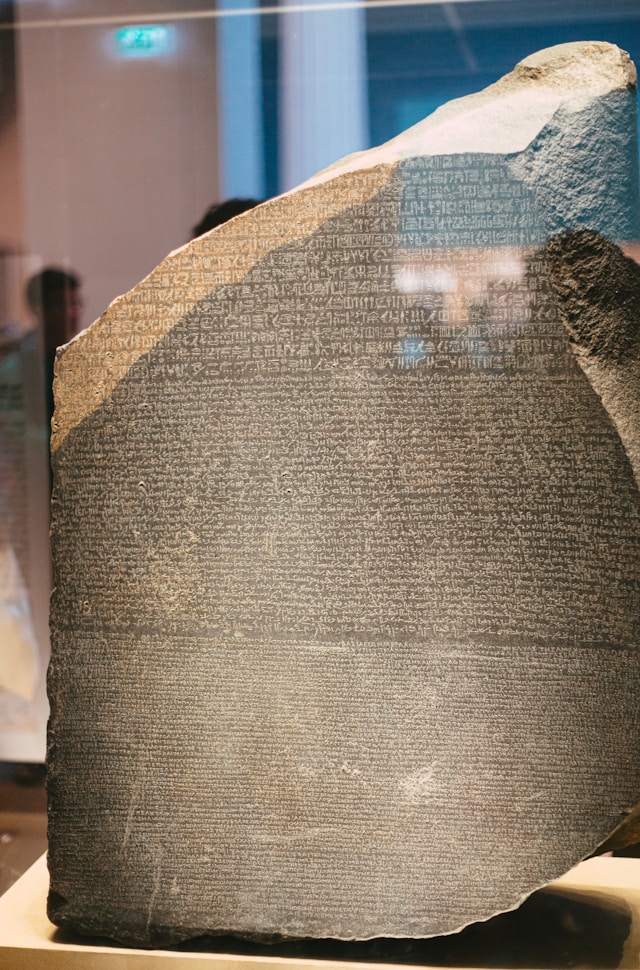

The radical democratization of writing occurred with the invention of the alphabet. Around 1800 BCE, Semitic-speaking people in or near Egypt took a small selection of hieroglyphs and repurposed them to represent individual sounds rather than concepts. This “Proto-Sinaitic” script was refined by the Phoenicians, a maritime trading culture.

Because the Phoenicians were the great merchants of the Mediterranean, their lean, 22-letter system spread like wildfire. It was efficient, easy to learn, and adaptable to different languages. The Greeks eventually added vowels. While, the Romans adapted the Greek alphabet into the Latin script, and the foundation for Western literacy was laid.

The shift from “idea-writing” to “sound-writing” meant that a person only had to memorize a few dozen shapes to record anything they could say.

Were there prehistoric writings?

The definition of prehistory excludes writing, as that era marks the time before written records existed. While Paleolithic and Neolithic peoples left behind rich visual traditions, none of these artifacts replicate the flow of continuous speech.

Sumerian and Egyptian scripts bridge the gap between prehistory and history; they record personal names, titles, and events in a system that mirrors spoken language rather than isolated symbols. That line is fuzzy, token systems and proto‑writing blur into writing proper, but the consensus is that full writing emerges only with or just before the first urban, state‑level societies.

Why complex societies needed writing

Writing appears where societies become too large and complex for memory and oral tradition to manage everything.

Key pressures included:

- Trade and accounting: Merchants and temple administrators needed to track inventories, rations, loans, and taxes across seasons and distances. Lists of barley, sheep, and silver are some of our earliest texts from Mesopotamia.

- Governance and law: Rulers used written decrees, legal codes, and administrative records to extend their authority beyond their immediate presence. Writing stabilized rules, standardized taxes, and made bureaucracies possible.

- Religion and ritual: Temples required receipts, land registers, and offerings lists even before large theological compositions; later, myths, hymns, and ritual instructions were copied as sacred texts. Writing fixed liturgies and preserved authoritative versions of religious narratives.

- Culture and identity: Over time, writing became the medium for historiography, literature, philosophy, and collective memory, allowing communities to anchor their past in durable narratives.

The most important tool of humanity

We often think of writing as a way to record history, but it is more accurate to say that writing created history. By externalizing the human mind, we turned our thoughts into a permanent infrastructure.

This silent technology remains our most powerful tool for synchronization, allowing billions of strangers to operate under the same laws, share the same stories, and contribute to a single, global conversation.