The fibers of civilization: a history of paper and the recorded word

Writing, in its earliest stages, was a heavy endeavor. To keep track of grain stores, celestial movements, or kingly decrees, ancient civilizations had to physically carve their thoughts into the Earth. In Mesopotamia, this meant wet clay tablets etched with reed styluses. In Egypt, it meant the laborious chiseling of stone. These mediums were permanent, but they were also immobile and difficult to scale.

The evolution of writing surfaces is the history of how human societies solved the problem of information density. As populations grew and the first cities emerged, the need for a portable, cheap, and durable medium became the primary bottleneck for progress.

The weight of knowledge: ancient writing materials

The Sumerians of Mesopotamia pioneered written communication around 3100 BCE using clay tablets. Scribes pressed wedge-shaped cuneiform marks into wet clay using reed styluses, then baked the tablets to preserve them. These tablets proved remarkably durable, thousands survive today. But their weight and bulk made them impractical for extensive record-keeping or transport.

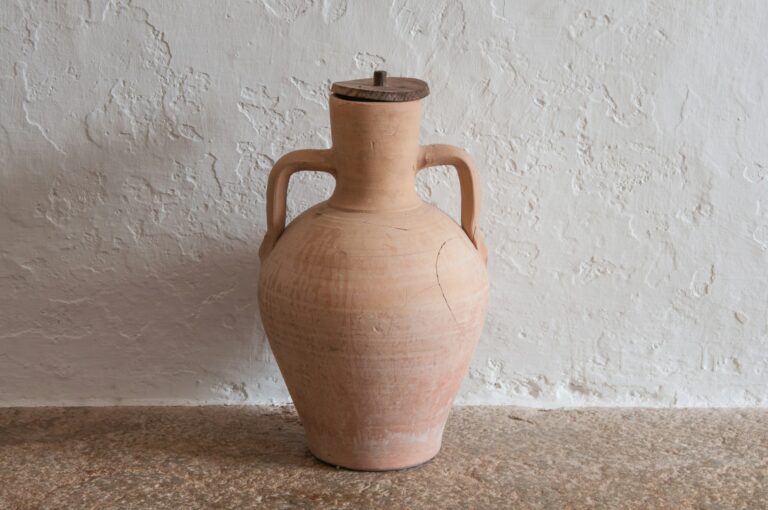

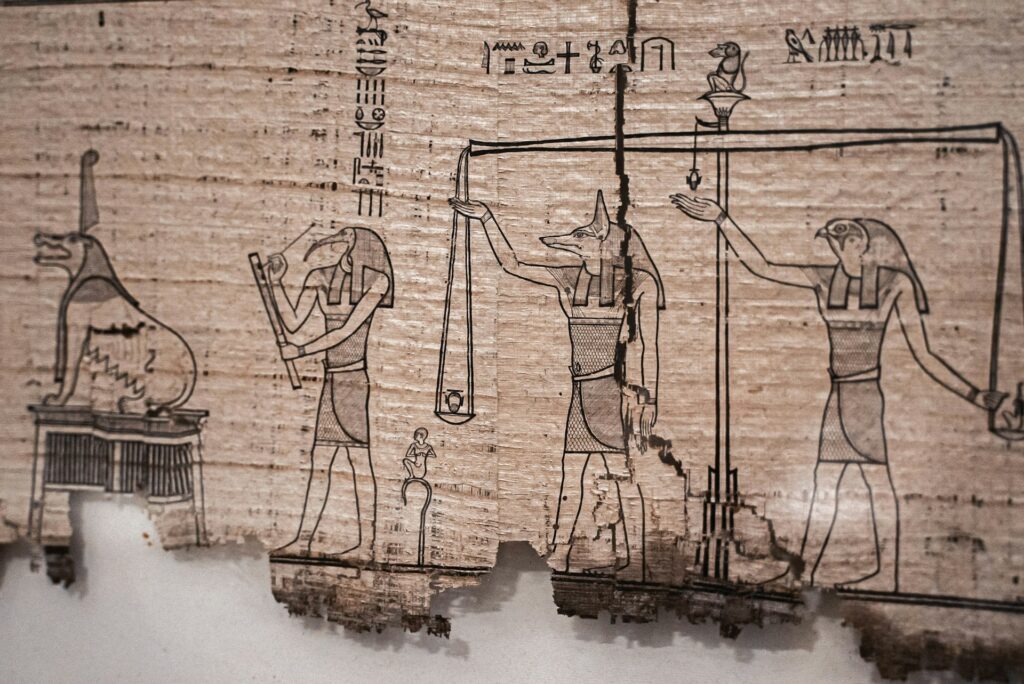

In Egypt, the discovery of papyrus around 3000 BCE marked the first major leap toward portability. By weaving the pith of the Cyperus papyrus sedge and beating it into sheets, the Egyptians created a surface that could be rolled into scrolls. It was light and flexible, allowing the Egyptian bureaucracy to manage a vast empire from a centralized location. However, papyrus was a regional monopoly. The plant grew almost exclusively in the Nile Delta, and the material was prone to rot in humid climates or crumble in the cold.

By the time the Roman Empire reached its height, parchment, made from the processed skins of sheep, goats, or calves, became the premium alternative. It was incredibly durable and could be folded into a “codex”, but it was prohibitively expensive. A single large Bible might require the hides of over 200 animals. Knowledge was literally bound in the skin of livestock, keeping literacy a luxury of the ultra-elite and the clergy.

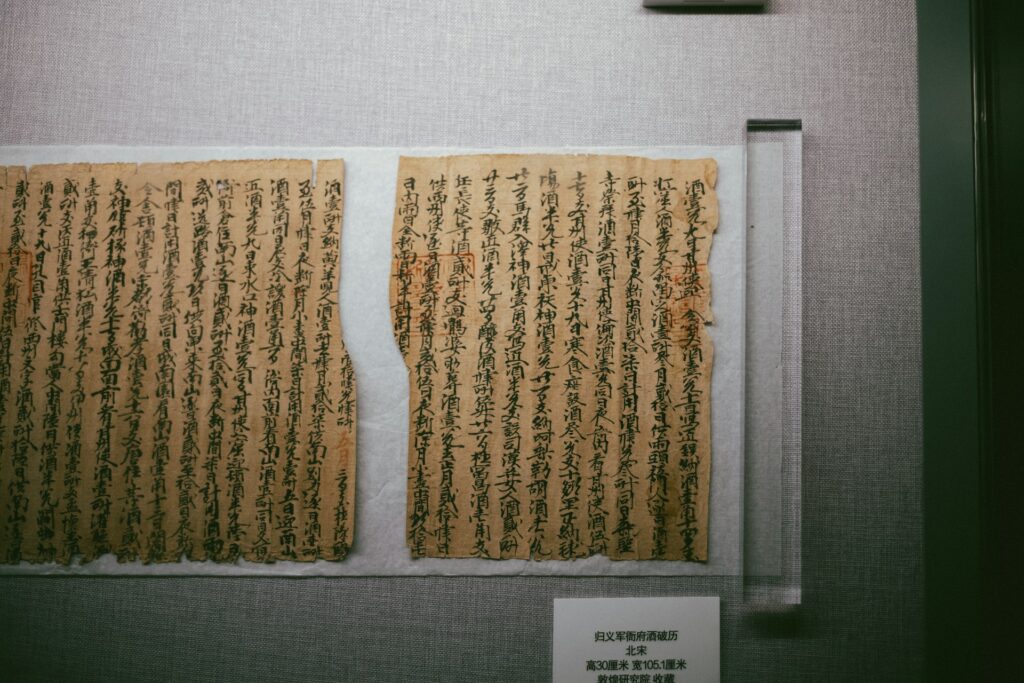

Ancient China developed its own tradition using bamboo strips and silk. Bamboo books consisted of narrow wooden slats bound together with cord. While silk provided a luxurious but expensive alternative. Both materials presented challenges: bamboo was heavy and cumbersome to transport, while silk’s high cost limited its widespread use.

Cai Lun and the invention of paper

The true invention of paper, occurred in China during the Han Dynasty. While archaeological evidence suggests primitive forms of paper existed earlier, the year 105 CE is traditionally cited as the turning point. Cai Lun, a court official, is credited with refining the process.

Unlike papyrus (which is a laminated plant) or parchment (which is skin), paper is a felted material. Cai Lun’s genius lay in breaking down raw fibers from mulberry bark, hemp, old rags, and even fishing nets into a pulp. By suspending these fibers in water and catching them on a screen, the water drained away, leaving a tangled mat of fibers that, once dried, became a lightweight, uniform sheet.

This was a technological disruption of the highest order. Paper was significantly cheaper to produce than silk. While being far more practical than the heavy bamboo slips used for everyday records. It allowed the Chinese imperial bureaucracy to expand its reach. Facilitating the civil service examinations that would define Chinese governance for centuries. Han dynasty officials used paper to produce detailed topographical and military maps with accurate scales, color-coding, and specific regional features.

Paper’s journey across continents

Chinese papermaking techniques reached Korea early in the first millennium CE and arrived in Japan around 610 CE. Japanese craftsmen refined the process using fresh bast fibers from mulberry trees, creating papers of exceptional quality through multiple rapid immersions of the mould. This technique produced the characteristic multi-layer fiber mat that gave Asian papers their distinctive appearance and durability. It was soft, absorbent, and ideal for brush calligraphy. It was integrated into every facet of life, used for windows, fans, and umbrellas.

The Islamic expansion eastward in the 7th and 8th centuries brought papermaking knowledge to the Arab world. Paper mills appeared in Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo. Arab papermakers adapted the process to local conditions, using rags rather than fresh plant fibers due to material shortages. They filtered pulp through reed screens and coated finished sheets with starch paste, producing papers with excellent writing properties.

This era, known as the Islamic Golden Age, saw an explosion of scientific and philosophical output. Because paper was affordable, libraries grew from containing a few dozen parchment scrolls to housing hundreds of thousands of paper volumes. The accessibility of the medium allowed for the preservation of Greek and Indian knowledge, which would later fuel the European Renaissance.

Paper finally reached Europe several centuries after its invention, arriving in Armenian and Georgian monasteries by 981 CE. But, it wasn’t until the 12th and 13th centuries that paper mills appeared in Spain and Italy. The rise of linen-based paper, made from recycled rags, dropped costs so low that it paved the way for Johannes Gutenberg. The printing press would have been a financial failure if it had to rely on expensive parchment.

The birth of paper money

Paper’s most revolutionary application emerged in China between the 7th and 10th centuries with the invention of paper currency. Tang dynasty merchants initially introduced private bills of credit around 900 CE to avoid transporting thousands of heavy copper coins across long distances. Merchants traded receipts from deposit shops where they had left money or goods, creating the world’s first negotiable instruments.

The Song dynasty government recognized paper money’s potential and nationalized the system in the 1020s. Producing the world’s first state-issued paper currency called jiaozi. Merchants in Chengdu printed these vouchers on paper made from bamboo bark, adding patterns, passwords, and seals to prevent counterfeiting. The purpose was practical: paper money facilitated large-scale commercial transactions and government expenditures without the logistical burden of metal coinage.

This required a massive social shift. For paper money to work, the population had to move from the metal to representative value (the promise of the state). Paper money was the ultimate tool of economic expansion, allowing for a level of liquidity that propelled China into a proto-industrial revolution.

The conditions for innovation

Several factors converged to make paper’s invention possible in Han Dynasty China. The empire’s sophisticated bureaucracy created enormous demand for writing materials that existing options couldn’t satisfy. Textile production provided abundant waste materials, rags and hemp remnants, that became paper’s raw ingredients. Chinese artisans had already developed expertise in processing plant fibers through silk production. Providing the technical knowledge base Cai Lun adapted.

Finally, paper required literacy and a “middle class.” As long as knowledge was reserved for the top 1% of society, parchment was sufficient. It was the rise of the merchant, the academic and the bureaucrat, people who needed to write every day but couldn’t afford a flock of sheep for every ledger. That made paper the essential substrate of the modern world.

The transition from stone to skin, and finally to fiber, represents the democratization of data. By making the medium cheap, the ancient world ensured that ideas could finally outlive the empires that recorded them.