The history of gears: from ancient mechanisms to industry

Gears transformed human civilization by converting rotational motion into power, precision, and possibility. These toothed wheels, meshing together to transfer force and alter speed, emerged across ancient societies and became the mechanical foundation for everything from astronomical instruments to industrial machinery.

The foundation: simple machines

Long before the first gear turned, ancient civilizations relied on a set of fundamental tools. These inventions served as the necessary precursors to the gear. The lever allowed humans to move weights far beyond their natural capacity. The wheel and axle reduced friction, making transportation across distances possible. The screw and the inclined plane provided ways to lift heavy loads with minimal effort.

Early engineers realized that these tools could be combined. Archimedes, the Greek mathematician, pioneered the study of these mechanics in the third century BCE. He famously demonstrated how a series of pulleys and levers could move an entire ship. These basic principles of leverage and rotation provided the intellectual framework for gears. The first toothed wheels likely emerged as ratchets on windlasses, designed to prevent heavy loads from slipping backward. Once engineers realized they could mesh two toothed wheels together, the gear was born.

The earliest gear artifacts

The earliest references to geared mechanisms trace back to ancient China around 3000 BCE, where legends describe the South-Facing Chariot. This device allegedly used a differential gear train with wooden pin teeth to maintain directional orientation across the shifting terrain of the Gobi Desert.

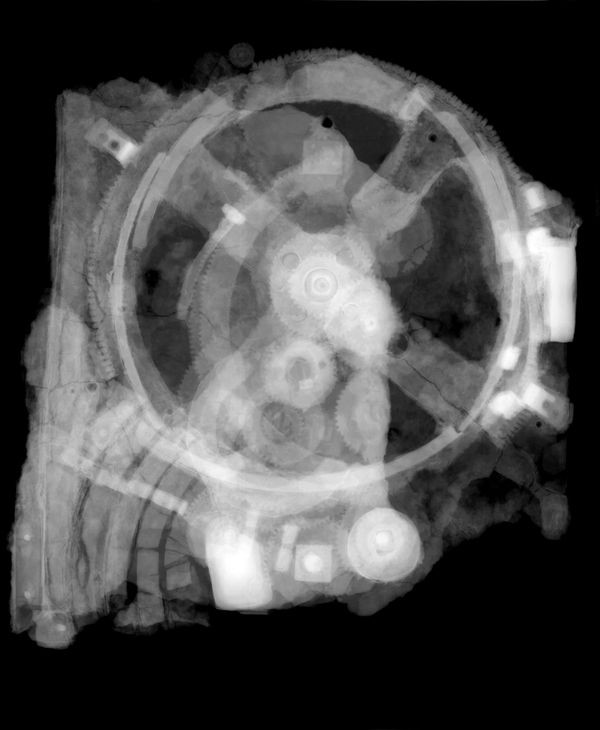

The oldest surviving geared artifact remains the Antikythera mechanism, recovered from a shipwreck off the Greek coast and dating to approximately 80 BCE. This bronze marvel contained 37 meshing gears that tracked lunar phases, predicted eclipses, and modeled the Moon’s irregular orbit with stunning accuracy. The mechanism’s complexity would remain unmatched for over a thousand years.

Why we need gears

Gears serve three primary functions: they change the direction of rotation, they change the speed of motion, and they multiply force, or torque. This utility makes them indispensable. Without gears, an engine would have to be connected directly to its output, which often results in inefficient or impossible operation.

The core principle of the gear is the mechanical advantage. When a small gear drives a larger one, the larger gear turns more slowly but with significantly more force. This allows a small amount of input energy, such as a person turning a crank or a stream of water, to move massive stones or heavy hammers and perfect for grinding grain. Conversely, a large gear driving a small one increases speed, which is vital for timekeeping and precision instruments.

The genius of gears lies in their ability to maintain constant contact, ensuring smooth power transmission without slippage. This reliability made them indispensable for applications demanding precision, from clock mechanisms to astronomical calculators. Without gears, humanity would have struggled to harness water power, measure time accurately, or build the complex machinery that defines modern life.

Astronomy and time

One of the most profound uses of gears in the ancient world was the measurement of the cosmos. In 1901, divers discovered the Antikythera Mechanism in a shipwreck off the coast of Greece. This device, dating back to the second century B.C., contained over thirty bronze gears. It functioned as an analog computer, predicting the positions of the sun, moon, and planets, and even tracking the dates of the Olympic Games.

The Antikythera mechanism demonstrated gears’ extraordinary capacity for modeling celestial movements. Its bronze gears predicted the Moon’s position with a modeled period of 27.321 days, nearly identical to the actual sidereal month of 27.321661 days. The device even incorporated pin-and-slot gears to account for the Moon’s varying orbital velocity, demonstrating knowledge of elliptical motion centuries before Kepler.

Gears allowed for the discretization of time. While sundials and simple water clocks were common, they lacked precision over long periods. Geared water clocks used a steady drip of water to turn a wheel, which then used a gear train to move a pointer across a dial. This transition from continuous flow to mechanical increments laid the foundation for the mechanical clocks of the Middle Ages.

Medieval tower clocks employed iron crown gears for timekeeping, bringing precise measurement to European cities. These mechanical timepieces relied on gear ratios to convert the steady descent of weights into the measured advance of clock hands, synchronizing daily life across growing urban populations.

Powering industry: watermills and smithing

Gears also revolutionized the way humans harnessed the power of nature. The Romans were masters of the watermill, using massive wooden gears to grind grain. The Vitruvian mill used a vertical waterwheel connected to a horizontal gear, which then drove the millstone. This setup allowed a single stream of water to do the work of dozens of animals.

As metalworking evolved, gears became essential in the transition from bronze to iron and steel. In the great smithies of the ancient and medieval worlds, water-powered gears drove heavy trip hammers and giant bellows. These machines allowed for the constant, high-pressure air needed to reach the temperatures required for smelting steel. Gears turned the constant rotary motion of a waterwheel into the rhythmic, linear strike of a hammer. This mechanization of metal production made tools and weapons more affordable and widely available, altering the course of warfare and agriculture.

Advances that enabled the invention of gears

The metallurgy behind gears

Gear technology depended entirely on advances in metalworking that preceded it. Bronze Age craftspeople mastered smelting around 3000 BCE, combining copper and tin in charcoal-fired furnaces to produce bronze. This alloy proved ideal for casting complex shapes, including the intricate gear teeth of the Antikythera mechanism.

The lost-wax casting method allowed metalworkers to create detailed bronze gears by sculpting patterns in wax, encasing them in clay, and pouring molten metal into the resulting molds. Later, Iron Age smiths developed bloomery furnaces capable of producing wrought iron, which could be forged into durable gear components and reinforcing bands.

The wheel turns first

Before gears could mesh, the wheel itself required invention. Mesopotamian potters developed true rotating wheels with axle mechanisms between 4200 and 4000 BCE. The oldest surviving wheel, found at Ur in modern Iraq, dates to approximately 3100 BCE.

This simple machine established the rotational principles that gears would later exploit. The invention of the wheel enabled pulleys, which combined with gears to create complex mechanical systems. Spoked wheels emerged around 3200 BCE, reducing weight while maintaining strength, a design philosophy that would eventually inform gear construction.

Society changes that built the machine

Gear technology flourished where several conditions converged. Advanced societies needed mathematical knowledge to calculate gear ratios and astronomical expertise to design instruments like the Antikythera mechanism. The device likely required teams of mathematicians, astronomers, and craftspeople working collaboratively, pooling generations of accumulated wisdom.

Bronze casting required established trade networks to obtain tin and copper, plus skilled artisans capable of precision work. Medieval Europe’s proliferation of geared watermills depended on social organization too: feudal systems that controlled water rights, monastic communities that pioneered industrial applications, and guilds that preserved millwright knowledge across generations.

Urban growth created demand for mechanical solutions to grinding, timekeeping, and textile production, while agricultural surplus freed specialists to develop technical expertise. The blacksmith became an indispensable partner, forging metal components that held wooden gears together and crafting iron spindles that transferred rotational power.

Seeds of revolution

Gears spent millennia in relative infancy, confined to specialized applications in mills, clocks, and scientific instruments, until the Industrial Revolution changed it. Steam engines, textile machinery, and factory equipment demanded mass-produced, high-quality gears.

Innovations like interchangeable parts, standardized sizes, and hardened steel construction transformed gears from artisanal products into industrial commodities, making them ubiquitous in everything from massive factories to tiny wristwatches of the 19th century.