The ancient origins of education

Education began the moment a human being realized that survival depended on the transmission of information across generations. For thousands of years, the invention of education was a slow, deliberate process of turning experience into data and data into power.

Education developed across multiple civilizations, each responding to practical needs: keeping records, training priests, preserving knowledge, and maintaining power structures. The invention of writing around 3500 BCE in Mesopotamia marked the beginning of formal education as we know it.

Writing: the foundation of everything

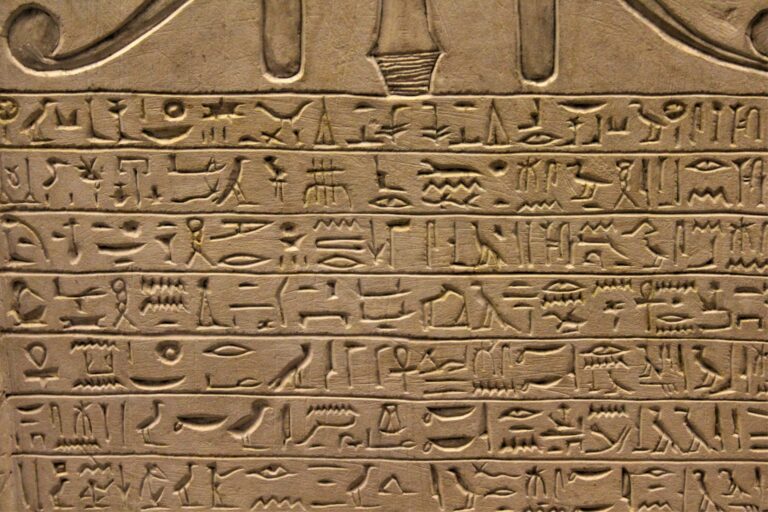

The Sumerians created cuneiform writing around 3200 BCE, initially as a system for recording transactions and goods. This breakthrough transformed human civilization. Without a way to preserve information beyond oral tradition, formal education couldn’t exist. Each civilization developed its own script: Egyptians used hieroglyphics, Chinese developed logographic characters, and Mesoamericans created their own complex writing systems.

Mastering these writing systems required years of dedicated study. In Mesopotamia, students practiced on clay tablets for hours daily, copying texts until they achieved perfection. The exact reproduction of scripts became the ultimate test of educational excellence.

Mesopotamia: schools born from commerce

Mesopotamian education began in temples but soon expanded to dedicated school buildings called “edubba”. The curriculum was rigorous: cuneiform script, mathematics, literature, and foreign languages including Sumerian and Akkadian.

Students were typically male children from wealthy families or those connected to royal courts. Priests dominated the intellectual domain, and libraries housed in temples became centers of learning. The education period was long and discipline harsh, with memorization, oral repetition, and copying serving as primary teaching methods.

Egypt: education as divine knowledge

While Mesopotamia used clay, Egypt utilized the Nile’s greatest gift: papyrus. The invention of a portable, flexible writing surface allowed education to become more expansive. In Egypt, education was deeply intertwined with religion and the preservation of the soul.

Kheti, treasurer to Mentuhotep II (2061–2010 BCE), founded the earliest known formal school during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. The school’s curriculum spanned from basic literacy and religion to advanced studies in law, medicine, and astrology.

Egyptian education was profoundly tied to religious institutions. Temples housed schools and libraries, with priests controlling access to knowledge. This system maintained social hierarchies, only the upper classes received formal education, ensuring power remained concentrated among the elite.

China: meritocracy through exams

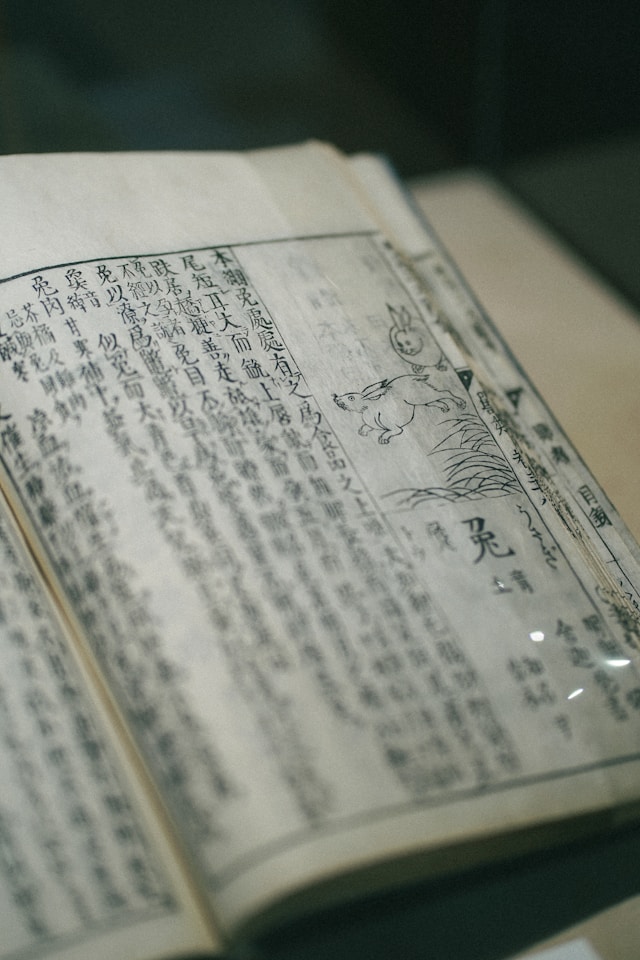

China’s approach to education was perhaps the most influential in terms of social structure. Ancient China created its first education system during the Xia dynasty (2076–1600 BCE ). By the time of Confucius (551–479 BCE), education had become the backbone of Chinese politics. Confucius argued that leadership should be based on merit and virtue, not just birthright.

The imperial examination system represented a revolutionary concept: meritocratic selection of officials based on knowledge of laws and principles rather than birth alone. These competitive exams occurred at local, provincial, and national levels, offering rare opportunities for social mobility. Success in examinations became the primary path to power, creating a highly literate elite sharing common values and cultural identity.

Greece: philosophy and critical thinking

Greek education differed fundamentally from its contemporaries. In city-states like Athens, education was largely private, with the state playing minimal roles except for military training. This decentralized approach fostered intellectual diversity.

Philosophy schools became Greece’s distinctive contribution. Plato founded the Academy around 387 BCE, emphasizing philosophy, mathematics, and dialectics. Aristotle established the Lyceum in 335 BC, promoting empirical observation and systematic classification. These institutions were attended by young intellectual elites. Almost exclusively upper-class men who had completed primary education and possessed financial freedom.

Greek education encouraged critical thinking, questioning, and exploration of moral and ethical concepts. Philosophical discussions and debates shaped students into thoughtful individuals, fundamentally different from the memorization-focused systems elsewhere.

India: the gurukula system

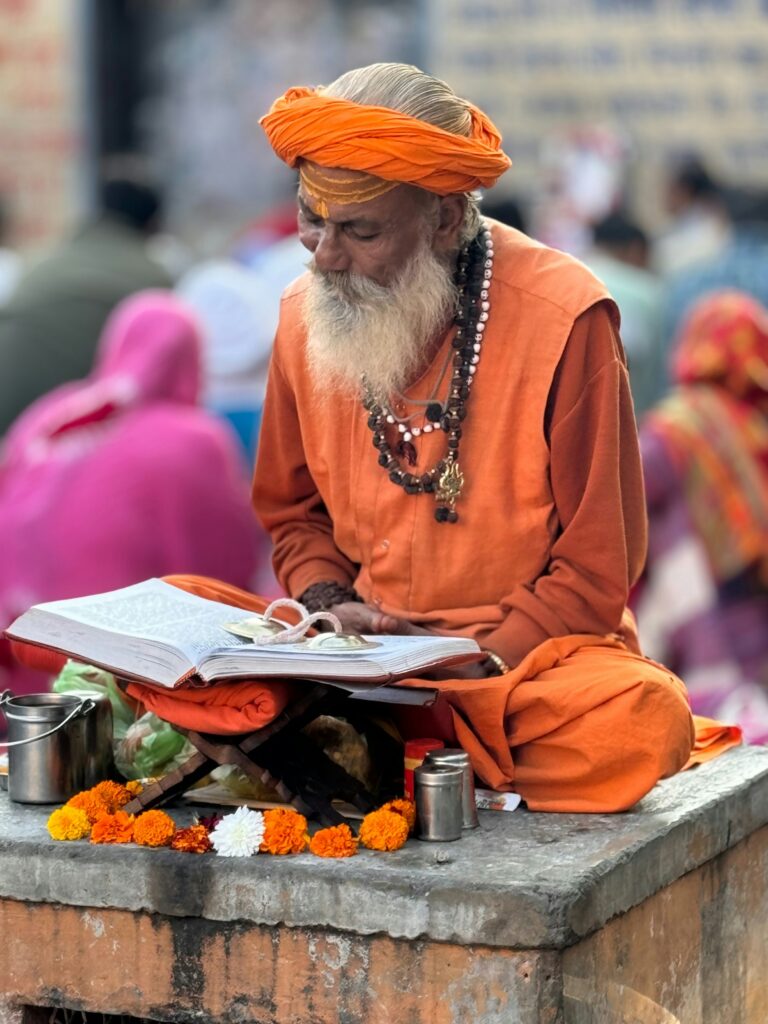

Ancient India developed the Gurukula system, during the Vedic period (c. 1500–500 BCE), where students lived with their guru (teacher) to receive education. The Brahmins, positioned at the top of the social hierarchy, controlled educational access. Education centered on Vedic knowledge transmitted orally, emphasizing religious texts, philosophy, and spiritual development.

Buddhist monasteries later emerged as alternative centers of learning. Nalanda University became a renowned institution attracting scholars from across Asia, demonstrating how religious institutions could foster intellectual exchange beyond rigid caste boundaries. The Indian system emphasized memorization of sacred texts and philosophical inquiry, preparing students for religious leadership and scholarly pursuits.

Central and South America: indigenous learning centers

In the Western Hemisphere, the Maya, Aztecs, and Incas developed sophisticated educational systems that rivaled anything in Eurasia. For the Maya and Aztecs, education was a mix of harsh military discipline and advanced scientific observation.

Aztec children attended different schools based on their social class: the Calmecac for nobles (priests and leaders) and the Telpochcalli for commoners (soldiers and tradesmen). Their education was heavily focused on the calendar, astronomy, and the complex rituals required to keep the sun moving.

In the South American Andes, the Inca lacked a written alphabet but utilized the “Quipu”, a system of knotted strings. Education in the Yachaywasi (House of Knowledge) taught elite students how to read these strings to manage an empire that stretched thousands of miles. It was a masterpiece of data management without a single drop of ink.

The pillars of learning: writing, paper, and time

Education was made possible by specific technological and social shifts.

Writing and Paper: Without a way to externalize memory, people can only learn what a single person remembers. The invention of writing (Cuneiform, Hieroglyphs, Alphabet) allowed civilizations to store knowledge. The shift from heavy clay and stone to papyrus, and eventually to the Chinese invention of paper (c. 105 CE), made knowledge portable and tradeable.

The Luxury of Time: Education requires “Scholè”, the Greek word for leisure. In early hunter-gatherer societies, everyone was busy finding food. It was the agricultural revolution and the creation of a food surplus that allowed a specific class of people (priests, scribes, and philosophers) the time to sit down and learn, often supported by stimulants like fermented drinks and later caffeine, which helped sustain long hours of study and record-keeping.

Religion: For most of human history, the temple was the first school. Religion provided the “Why” for education, the need to understand the gods, the stars, and the moral law. It created the first structured environments where disciplined study was encouraged.

The evolution of the mind

The origins of education is a map of human ambition. It moved from the practical need to count sheep in Sumer to the philosophical need to define justice in Athens. Each civilization contributed a different layer: the bureaucracy of China, the spiritual discipline of India, and the civic participation of Greece. By the time the printing press arrived in the 15th century, the foundation had already been laid by thousands of years of scribes, monks, and philosophers.

Civilizations created education as they became complex enough to require record-keeping. Elites used it to preserve power by controlling knowledge, while new technologies allowed them to store information beyond human memory. This process ensures that one generation does not lose what it has learned to the next.