The engineering of ancient water systems

In the earliest days of human settlement, if you wanted water, you lived beside it. The great cradles of humanity, Sumer, Egypt, the Indus Valley, were defined by their proximity to floodplains. However, as populations increased, the limitations of the riverbank became a bottleneck for progress. To grow, humanity had to learn how to make water move.

The transition from basic irrigation to the sophisticated architectural marvels of the Roman aqueduct represents one of the most significant technological leaps in history.

Canals and the birth of irrigation

The story of water transport begins not with stone arches, but with dirt. Around 6,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, the Sumerians realized that the unpredictable flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates could be harnessed. They dug rudimentary ditches to channel overflow into thirsty fields.

These early canal systems were the first instance of humans redirecting a natural resource toward a specific goal. While these systems were primarily agricultural, they laid the groundwork for urban planning. By creating a predictable water supply, the Sumerians allowed the first cities, like Uruk, to sustain thousands of inhabitants.

In Egypt, the basin irrigation system took this a step further. By creating a network of earthen banks that could trap the Nile’s receding floodwaters. The Egyptians effectively stored the river. Yet, these systems were still horizontal and highly dependent on the seasonal pulse of nature. The real breakthrough required moving water across distances and elevations where nature never intended it to go.

The first aqueduct system

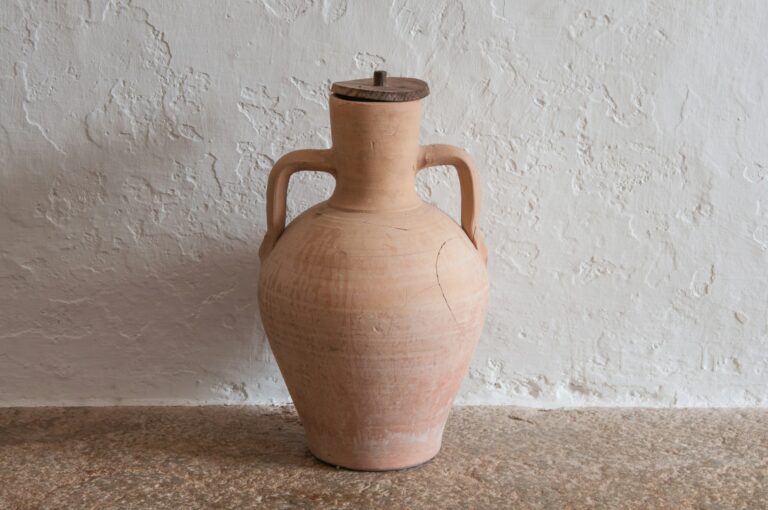

Around 2000 BC, the Minoan civilization on Crete developed what historians now recognize as humanity’s first aqueduct systems. The Palace of Knossos featured closed pressurized pipe systems made from terracotta that exploited hydraulic principles like the siphon effect and communicating vessels. Water traveled through underground channels, maintained pressure through clever engineering, and supplied multiple levels of palatial complexes with running water.

The Minoans understood something fundamental: water seeks its own level. Their aqueducts used bridge structures with precise inclination rates to move water efficiently while maintaining flow. Clay pipes carried water over distances, protected from contamination and evaporation by their underground placement.

The Qanat: persia’s hidden revolution

Before the Roman arch dominated the landscape, the Persian Empire (around the 7th century BCE) developed one of the most ingenious water technologies ever devised: the Qanat.

A qanat is an underground tunnel that taps into groundwater at the foot of a mountain and carries it miles across arid plains using a precise, gentle slope. Because the water travels underground, it doesn’t evaporate in the blistering heat.

The invention of the qanat changed the social fabric of the Near East. It allowed for the creation of “oasis cities” in the middle of deserts. The technology required a sophisticated understanding of geology and surveying. Workers would dig vertical shafts at regular intervals to provide ventilation and a way to remove excavated soil. Some of these tunnels stretched for thirty miles, a feat of endurance and mathematical precision that proved water could be mined as effectively as gold.

The rise of the aqueduct: engineering gravity

While the Greeks introduced the use of siphons and lead piping to navigate hilly terrain, it was the Romans who perfected the aqueduct. The word itself comes from the Latin aqua (water) and ducere (to lead).

Between 312 BCE and 226 CE, the city of Rome was supplied by eleven major aqueducts. These systems fueled the massive public baths, the ornamental fountains that displayed imperial wealth, and the industrial-scale mining that powered the economy.

The Roman innovation was the mastery of the constant gradient. To keep water flowing over dozens of miles, the channel (or specus) had to drop a few inches for every hundred yards. If the slope was too steep, the water would erode the stone, if it was too shallow, the water would stagnate.

To maintain this pitch across valleys, the Romans built the iconic multi-tiered stone arches we see today. However, it is a common misconception that all aqueducts were above ground. In reality, about 80% of the Roman water network was buried to protect it from contamination, heat, and enemy sabotage.

The technology of flow: siphons and cement

The sheer scale of these systems was made possible by several key technological advancements:

- The Arch: By using the arch, Roman engineers could bridge massive gaps with minimal material. Allowing wind to pass through and preventing the structure from collapsing under its own weight.

- Pozzolanic Concrete: This “super-material,” made from volcanic ash, allowed the Romans to build structures that were waterproof and incredibly durable. They used a lining called opus signinum, a mixture of crushed tiles and mortar, to ensure the water channels didn’t leak.

- The Inverted Siphon: When a valley was too deep for an arched bridge, engineers used lead pipes to create a “U” shape. The pressure generated by the water falling down one side would push it up the other, provided the exit point was lower than the entry.

Social structures that made aqueducts possible

These projects demanded organized societies capable of mobilizing massive labor forces and resources. Aqueduct construction took years, sometimes decades, and employed thousands of workers. Only centralized states could command such efforts.

Wealth concentration mattered too. While public aqueducts served entire populations, wealthy individuals could afford private connections extending directly to their estates. This pattern appears across civilizations: public infrastructure serving communal needs while accommodating private extensions for elites.

During democratic periods, Greek water management focused on small-scale, cost-effective systems. Oligarchic periods saw emphasis shift toward large-scale hydraulic projects including major aqueducts. Political structure directly influenced infrastructure approach and scale.

The catalyst for urban growth

The impact of these transport systems on the growth of the first cities cannot be overstated. Before the aqueduct, the size of a city was hard-capped by the local well or the nearest stream. Once water could be imported, cities exploded in size.

Rome grew to a population of over one million people, a density that would not be seen again in Europe until the Industrial Revolution. This concentration of people allowed for the specialization of labor, the blooming of the arts, and the consolidation of military power.

Without the ability to move water, the sprawling urban centers of the ancient world would have remained small, fragmented villages. The aqueduct transformed the landscape, turning deserts into gardens and allowing humanity to cluster together in numbers that changed the course of history forever.