The history of oils and animal fats in human civilization

Oils and animal fats have been with us since the first bonfires. But their roles have shifted constantly. From marrow scooped out of bones to global commodities that lit cities, fed empires, and scented the bodies of the elite.

Long before the first bronze was forged or the first script was carved into clay, human survival depended on a mastery of lipids. They provided the light that extended the day into the night, the sealants that made ships seaworthy, and the sacred mediums that bridged the gap between mortals and their gods. Understanding the evolution of these substances is to understand the technical and social infrastructure of civilization itself.

From marrow and grease to the first presses

Long before agriculture, hunter‑gatherers prized fat as much as meat. Archaeological “kill sites” and bone assemblages suggest that early humans deliberately cracked long bones to access fat from carcasses. Treating it as a dense energy reserve rather than a by‑product. In many Pleistocene and early Holocene contexts, cut‑marks and burning patterns indicate roasting and boiling techniques that would naturally produce liquefied animal fat. Probably used both as food and as a primitive waterproofing or skin treatment.

By the Neolithic, the domestication of sheep, goats, and cattle provided a steady supply of tallow and lard. In China, early texts and later reconstructions indicate that animal fats were widely used by elites for cooking and also for sacrificial offerings, showing how quickly fat moved from pure subsistence to status and ritual. Similar patterns hold in the ancient Near East, where animal fats appear in lists of offerings and temple rations, interwoven with cereals and beer as staples of institutional life.

The first oils: cities, orchards, and stone technology

True vegetable oils, liquid at room temperature, only become common once permanent settlements and orchards appear. The Sumerians and the inhabitants of the Indus Valley were among the first to systematically extract oil from seeds, specifically sesame. By 3000 BCE, sesame oil powered the kitchens and lamps of Ur and Babylon.

Meanwhile, in the humid climates of West Africa, early populations mastered the extraction of palm oil. A substance so vital it dictated the migration patterns of Bantu-speaking peoples. These early civilizations recognized that lipids were the ultimate preservative. They protected skin from the sun and prevented grain-based foods from spoiling.

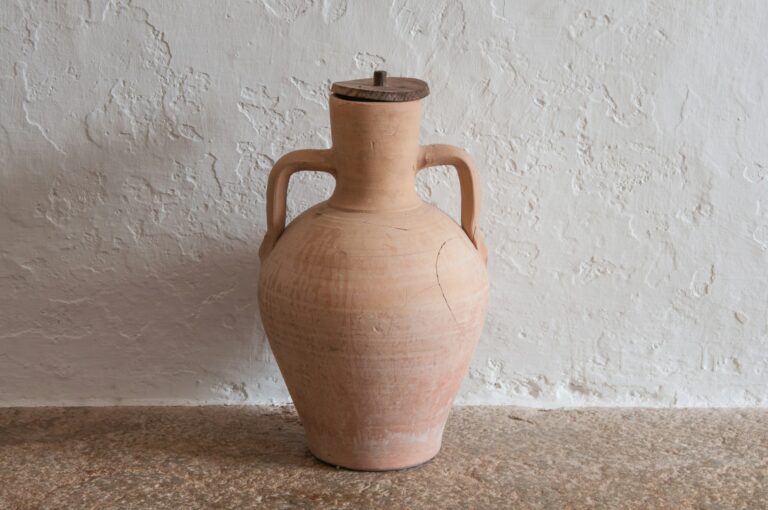

In Egypt, tomb finds include jars bearing residues of olive, palm, and possibly coconut oils. It suggests both imported and local sources. While textual and archaeological evidence indicates that ordinary cooking still relied heavily on animal fats. The division is telling: pressed oils, labor‑intensive and portable, gravitated toward ritual, cosmetics, and high‑status uses. While cheaper rendered fat stayed closer to the kitchen and the workshop.

The mediterranean engine: olive oil and maritime power

No single substance defined the classical world more than olive oil. While the wild olive existed for millennia, its systematic cultivation began in Crete and the Levant around 2500 BCE. The Minoans and later the Phoenicians transformed olive oil from a local foodstuff into a global currency.

The olive tree was a unique economic engine because it thrived in rocky, marginal soil where wheat could not grow. This allowed civilizations like the Greeks to colonize the Mediterranean. They traded their surplus oil for the grain of Egypt and the Black Sea. The Phoenicians, the master mariners of the era, designed specialized ceramic amphorae to transport oil across vast distances.

Oils as a bridge to the divine

Beyond the marketplace, oils held a profound metaphysical significance. The very word “Christ” is derived from the Greek Christos, meaning “The Anointed One.” In ancient Israel, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, the pouring of oil over a leader’s head was the physical manifestation of divine choice.

The Egyptians perfected the art of steeping aromatic flowers in animal fats or oils to create the world’s first perfumes and medicines. In their culture, fats were essential for the journey to the afterlife. Mummification relied heavily on cedar oil and resins to arrest the process of decay. This ritual use created a massive demand for exotic oils, fueling trade routes that stretched into the heart of Africa and across the Indian Ocean. The social condition of the elite was often defined by their access to these refined, scented lipids. Which served as a marker of status.

Continental variations: palms, seeds, and blubber

As civilizations branched out, the materials used for oils reflected the local ecology. In Ancient China, the Han Dynasty developed sophisticated presses to extract oil from soy and tea seeds. Which became essential for both cooking and waterproofing the paper umbrellas and silk robes of the nobility.

In the Americas, the absence of large domesticated livestock led to a different path. The Aztecs and Mayans utilized the fat of the avocado and the oil of the cacao bean. Further north, the Inuit and other Arctic peoples developed a “blubber economy.” Seal and whale fat were the structural foundation of life in the permafrost. Providing heat, light, and a vitamin-rich diet in an environment devoid of trees or vegetation.

The mechanics of extraction of oils

The evolution of oil was fundamentally a history of mechanical engineering. Early extraction was a violent process: seeds were crushed between heavy stones or trodden by foot. However, as the demand for olive and seed oils grew, so did the complexity of the machinery.

The Greeks introduced the lever-and-weight press, which used massive timber beams to exert several tons of pressure on stacks of woven baskets filled with olive pulp. By the Roman era, the invention of the screw press allowed for a more efficient and continuous extraction process. These technological advancements required a specialized class of laborers and engineers, leading to the rise of “industrial zones” in Roman North Africa and Iberia. Where massive batteries of presses produced hundreds of thousands of liters of oil for the Empire’s urban centers.

How oils and fats powered civilization

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the scale of oil use reached a fever pitch. The Enlightenment was, quite literally, fueled by the slaughter of whales. The sperm whale, in particular, provided spermaceti. A high-quality oil that burned with a bright, smokeless flame and served as a superior lubricant for the fine machinery of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution.

This period saw the rise of the first truly global oil industry, with American and European whaling fleets scouring the Pacific. However, the reliance on animal fats reached a hard ecological limit. The near-extinction of whale populations coincided with the discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania in 1859. This pivot shifted the world’s focus from biological lipids to mineral ones, forever changing the human relationship with the natural world.

The reliance on animal fats and plant oils remains one of the most consistent threads in the human experience. From the grease-painted faces of prehistoric hunters to the complex triglycerides in modern pharmaceuticals, these substances have acted as the friction-reducing agent of human progress.