The urban revolution: from neolithic villages to the first cities

As hunting and seasonal migration gave way to settled agriculture, humans entered the Urban Revolution. Permanent dwellings merged into the first cities, marking the moment we stopped merely inhabiting the world and began reshaping it.

Cities began as experiments in living densely together, and those first clusters of mud-brick and timber rewired how humans thought about work, belief, and power. They were the outcome of specific peoples, technologies, and landscapes coming together at just the right moment.

From villages to cities

For most of human history, small, mobile bands moved with game and seasons, leaving only light traces on the land. The shift toward permanent settlements began in the Neolithic. When domesticated plants and animals made it possible to stay put and store surplus food. Around fertile rivers and plains, villages grew denser and more complex until some crossed an invisible threshold: they became cities. With specialized work, shared infrastructure, and layered social hierarchies.

This process unfolded first in places like the Levant and Mesopotamia. Where early proto‑cities such as Jericho and later true cities such as Uruk emerged. Jericho in the Jordan Valley shows massive stone walls and a tower as early as the 9th millennium BCE. Signaling organized labor and a concern with defense or ritual beyond basic survival.

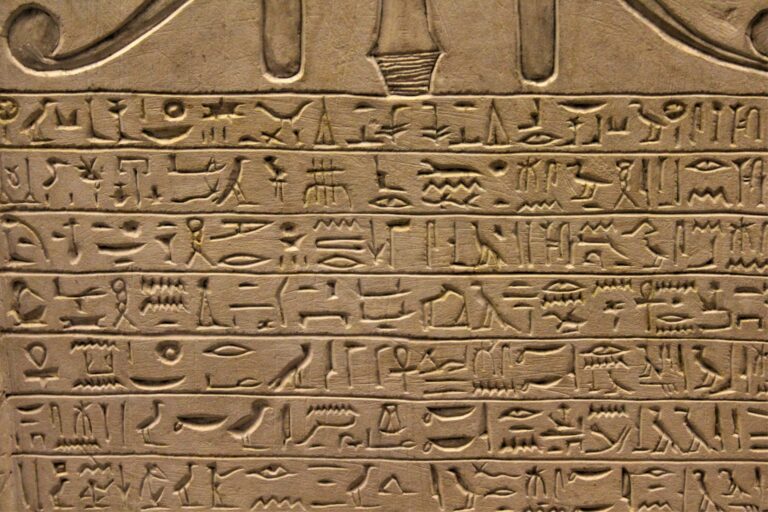

By the 4th millennium BCE in southern Mesopotamia, Uruk concentrated tens of thousands of people around monumental temples, complex bureaucracy, and some of the earliest writing.

The people who built the first cities were innovators of social engineering. To live in close proximity with hundreds, and eventually thousands, of people required a complete overhaul of human psychology.

It demanded the creation of hierarchy, the specialization of labor, and the development of “stranger-altruism”, the ability to coexist with people outside of one’s immediate kin group. In these early mud-brick enclosures, the concepts of priesthoods, kingship, and bureaucracy were born. Providing the structural scaffolding that allowed these burgeoning populations to function without descending into chaos.

The city as an engine of culture and commerce

The importance of the early city cannot be overstated; it was the primary catalyst for the acceleration of human progress. Before the city, trade was a sporadic exchange of high-value items like obsidian or sea shells. With the advent of urban centers, the city became a terminal. It was a central node where surplus grain could be traded for timber, copper, and precious stones. This economic density birthed the merchant class and, perhaps more importantly, the need for record-keeping.

Culturally, the city acted as a pressure cooker. When you bring diverse groups of people together, ideas collide. The city became the site of the first organized religions, where communal temples served as the focal point of civic identity. It was here that the first monumental architecture rose toward the heavens, signaling to the surrounding world that a group of people had mastered their environment and possessed the collective will to leave a permanent mark on the landscape.

Çatalhöyük: the honeycomb of the anatolian plain

Among the earliest experiments in urban living, Çatalhöyük stands as a fascinating anomaly. Located in modern-day Turkey and flourishing around 7500 BCE, it challenged our modern definitions of what a city looks like. Unlike the Sumerian cities that would follow, Çatalhöyük had no streets, no plazas, and no grand palaces.

Instead, the city was a dense, honeycomb-like cluster of mud-brick houses built directly against one another. To move through the city, residents walked across the rooftops, entering their homes through holes in the ceiling via wooden ladders. This “vertical street” system provided a unique form of security and thermal insulation.

What truly sets Çatalhöyük apart was its seemingly egalitarian nature. Archaeological evidence suggests a lack of significant social stratification; the houses were remarkably similar in size and layout. Inside, the walls were adorned with vibrant murals of leopards, vultures, and geometric patterns, and the dead were buried beneath the floors of the living rooms. It was a proto-city that prioritized communal cohesion and ancestral connection over the rigid hierarchies that would define the later metropolises of the Bronze Age.

A global genesis: the first cities by continent

Identifying the very first city on each continent is tricky, because “city” is a moving target and archaeological visibility is uneven. Still, a few early urban centers often stand in as continental pioneers.

- Asia (Mesopotamia): Uruk, in modern-day Iraq, is often cited as the world’s first true city. By 3200 BCE, it housed perhaps 50,000 people. It featured massive defensive walls and the iconic Ziggurats, proving that the city had become a center of both military and spiritual power.

- Africa: Memphis served as the first capital of a unified Egypt. Founded around 3100 BCE near the Nile Delta, it was the administrative heart of the Old Kingdom, managing the vast agricultural wealth generated by the river’s annual floods.

- South America: In the Supe Valley of Peru, the city of Caral rose around 2600 BCE. It is notable for its massive platform mounds and circular plazas, built centuries before the invention of pottery in the region, fueled instead by a complex trade in cotton and dried fish.

- North America: The Olmec city of San Lorenzo (c. 1200 BCE) in modern-day Mexico represents the first major urban center in Mesoamerica. It is famous for its colossal stone heads and sophisticated drainage systems.

- Europe: The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture in modern-day Ukraine and Romania built “mega-sites” like Talianki around 3700 BCE. These were massive, planned settlements of thousands of houses arranged in concentric circles, though they were periodically burned and rebuilt in a ritual cycle.

Technologies and ideas that made cities possible

The leap from village to city was bridged by several key technological advancements. The most critical was irrigation. By learning to divert river water through canals and dikes, early farmers could produce a massive surplus of food. This surplus allowed a portion of the population, priests, artisans, and soldiers, to stop farming and start specializing.

This specialization created social hierarchy and governance. Councils, chiefs, and kings coordinated large projects like irrigation systems, walls, and temples. They also extracted taxes, organized labor, and claimed ritual authority. Made possible by the invention of time and writing to track rations, land, and offerings, binding the city together through records and contracts.

Metallurgy also played a vital role. The transition from stone tools to bronze allowed for more efficient agriculture and more formidable defenses. Meanwhile, the development of pottery and storage technologies meant that wealth could be accumulated and protected from pests and rot. Finally, the wheel and the sailing vessel transformed the city from an isolated outpost into a connected hub, linking distant resources to the urban core.

Trade, culture, and the long shadow of early cities

The creation of the city changed the trajectory of the human species forever. It effectively ended the era of biological evolution as our primary means of adaptation and replaced it with cultural and technological evolution. In the city, we created a new kind of environment that shielded us from the whims of nature while exposing us to the complexities of social living.

Once cities appeared, they quickly became anchors in wider networks of exchange. Urban markets concentrated surplus grain, textiles, and crafted goods, attracting traders from surrounding villages and distant lands.

Inside their walls cities fostered dense cultural contact. Temples hosted festivals that brought thousands together at once, reinforcing shared myths and rituals. Artists, scribes, and specialists clustered near patrons, creating distinctive visual styles, literary traditions, and scientific knowledge.

The impact on civilization runs in both directions. Cities made large, complex societies possible by concentrating labor, authority, and information; at the same time, they made new forms of inequality, crowding, and conflict almost unavoidable. Çatalhöyük’s low‑profile, household‑centered density and Uruk’s temple‑dominated skyline are two early answers to the same tension: how to live together at scale without losing the thread of what binds people into a community at all.